Tuesday, 30 December 2008

Preliminary Animatic

Better late than never, here's a copy of my animatic as it stood about 2 weeks ago.

Soundtrack, dialogue and effects are placeholders to be replaced in the near future.

Likewise, character/location designs are not final.

Hopefully this will the first in a progression of videos as my animatic and subsequent animation are completed over the coming weeks.

Placeholder music Copyright Pearl Jam, Type O Negative and Test Switch Isolator (repsectively).

Monday, 29 December 2008

"Heroes" Eyes

A small observation thats been great for developing my film's lead character is the significance of eyes in anything associated with superheroes, whether in Western/Eastern animation, comic books or television.

I call it the Peter Petrelli face and anyone who's familiar with US tv show Heroes will know what I mean.

This is Peter Petrelli.

The second image is Peter's anti-hero alter ego from the future. We know he's from the future because he has a scar on his face and gets angry a lot. Still the same face though.

Other characters use it too, a kind of angry, confused, constantly-furrowed eyebrow.

These eyes are great for expressing a wealth of emotions in a single glare; anger, confusion, intention etc. Similarly, the wider the eye is opened the more wild a stare becomes. This is great for making a character seem out of place, confused or insane, though sinister characters tend to keep theirs more tightly closed.

Sometimes the eyes go a little out of control.

Great reference for character expression and emotion because its already hilarious.

This expression appears in anime/manga as well. From it we can gauge a character clearly means business, but variations on the shape of the brow tell us what buisness i.e. good or evil.

Shohen Jump's Naruto for example:

Predominently, a longer thinner eye denotes a more sinister character, thus the wider the eye, the more we associate them with good, or at least confusion. This is apparent in the cast of Heroes too. Compare evil character Sylar's eyes to good guy Peter's. There's a big, symbolic difference, one that I hope to make use of in the unforgivingly near future.

I call it the Peter Petrelli face and anyone who's familiar with US tv show Heroes will know what I mean.

This is Peter Petrelli.

The second image is Peter's anti-hero alter ego from the future. We know he's from the future because he has a scar on his face and gets angry a lot. Still the same face though.

Other characters use it too, a kind of angry, confused, constantly-furrowed eyebrow.

These eyes are great for expressing a wealth of emotions in a single glare; anger, confusion, intention etc. Similarly, the wider the eye is opened the more wild a stare becomes. This is great for making a character seem out of place, confused or insane, though sinister characters tend to keep theirs more tightly closed.

Sometimes the eyes go a little out of control.

Great reference for character expression and emotion because its already hilarious.

This expression appears in anime/manga as well. From it we can gauge a character clearly means business, but variations on the shape of the brow tell us what buisness i.e. good or evil.

Shohen Jump's Naruto for example:

Good.

Predominently, a longer thinner eye denotes a more sinister character, thus the wider the eye, the more we associate them with good, or at least confusion. This is apparent in the cast of Heroes too. Compare evil character Sylar's eyes to good guy Peter's. There's a big, symbolic difference, one that I hope to make use of in the unforgivingly near future.

Saturday, 6 December 2008

Inspiration Continues

Now that my animatic is beginning to take shape, I have realised the importance of understanding the effect visual style will have on both my film's impact and its strength. Essentially, careful design and planning will ensure that my characters are able to perform wanted actions within their environments and are not restricted by either limited design or poorly constructed set pieces. I was inspired to write this entry after reading John K's recent blog posts on the subject of "solid drawing", which can be found here: http://johnkstuff.blogspot.com/.

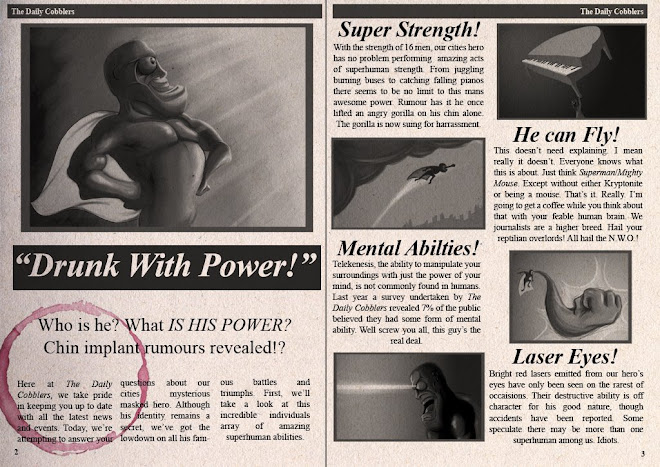

My initial research into comic book illustration and design left me perplexed as to how this aesthetic may be translated to animation. During the 1960's, this was tried with many famous superheroes, albeit with hilarious results.

Mighty Thor(1966) :

Iron Man (1966):

The Hulk (1966):

As massively limited animations disguised by flashy visual effects, these adaptations are not much different to an actual animatic. There are loads of examples of this type of super limited animation for comic book adaptations that were limited either by budget or the impossible task of making their characters move convinicingly in 3D space. These designs are occaisionally so obsessed with 'realism' that the animation becomes stiff and ironically far less life like. The unpredictable lines that make up the 3d forms of the character's grotesquely detailed anatomy are restricted to simply moving around the screen rather than metamorphosising. Lines of action are lost, squash and stretch becomes too 'cartoony' and characters are made to look like manakins. This trend didn't go away.

He-Man (1983):

X-Men (1992):

(Xmen had possibly the greatest cartoon theme music ever.)

Loonatics (2005):

Sure enough the animation quality improved over time, but arguably only because of the technology behind it. As the technolgy improved, so did the flashy visual effects. Fundamentally, many of the shows like those above are limited by their character designs. In Loonatics Unleased for example, although the models are slightly more dynamic, the character's faces only seem to exist at any one of three angles - front, 3/4 or side. All 177 degrees between these angles are sullied by the design's lack of 3D clarity as illustrations, so really this is no different to the limited animation comic adaptations of the 1960's.

The irony of it all is that a decade before, during the 1950's, animation purposefully adapted to this type of 'limited' aesthetic, but much more intelligently, where modern art became a major influence. This design focussed aesthetic really appeals to me because the animation becomes more of a collage than a series of drawings and draws attention to the medium itself, so can be both charming or abstract.

These concept illustrations for Disney's 101 Dalmations (1961) disregard geometric concepts to purposefully create images that break drawing principles, such as perspective and form, but in doing so draw attention to the idea itself, allowing the viewer to enjoy translating these bizarre images. Colours are also very carefully selected and restricted to a fitting palette that doesn't detract from the mood of the image, or seem obscure. To me, the best part of it all is that this rule breaking was completely intentional and not the result of poor design or construction. This allowed the animators much more freedom to experiment and create dynamic characters and actions, unlike in Loonatics.

Several contemporary superhero cartoons have made great use of this aesthetic, such as in these layout design's for Samurai Jack (2001) by painter Lou Romano.

Or for concept work in The Incredibles (2004).

I love how the chaotic nature of the images from Samurai Jack really emphasise the dreadful monolithic structures on which they focus, distorted, jagged and threatening, with loud, but limited colours that grab attention. Similarly, these concept images from the Incredibles effortlessly translate ideas to an observer in a glance, without the need for extreme detail.

In the end, this idea for an aesthetic may only apply to my layout designs and not to characters, but this is still undecided. As this week progresses I hope to upload some experiments with these ideas in order to finalize both my film's visual style and designs.

My initial research into comic book illustration and design left me perplexed as to how this aesthetic may be translated to animation. During the 1960's, this was tried with many famous superheroes, albeit with hilarious results.

Mighty Thor(1966) :

Iron Man (1966):

The Hulk (1966):

As massively limited animations disguised by flashy visual effects, these adaptations are not much different to an actual animatic. There are loads of examples of this type of super limited animation for comic book adaptations that were limited either by budget or the impossible task of making their characters move convinicingly in 3D space. These designs are occaisionally so obsessed with 'realism' that the animation becomes stiff and ironically far less life like. The unpredictable lines that make up the 3d forms of the character's grotesquely detailed anatomy are restricted to simply moving around the screen rather than metamorphosising. Lines of action are lost, squash and stretch becomes too 'cartoony' and characters are made to look like manakins. This trend didn't go away.

He-Man (1983):

X-Men (1992):

(Xmen had possibly the greatest cartoon theme music ever.)

Loonatics (2005):

Sure enough the animation quality improved over time, but arguably only because of the technology behind it. As the technolgy improved, so did the flashy visual effects. Fundamentally, many of the shows like those above are limited by their character designs. In Loonatics Unleased for example, although the models are slightly more dynamic, the character's faces only seem to exist at any one of three angles - front, 3/4 or side. All 177 degrees between these angles are sullied by the design's lack of 3D clarity as illustrations, so really this is no different to the limited animation comic adaptations of the 1960's.

The irony of it all is that a decade before, during the 1950's, animation purposefully adapted to this type of 'limited' aesthetic, but much more intelligently, where modern art became a major influence. This design focussed aesthetic really appeals to me because the animation becomes more of a collage than a series of drawings and draws attention to the medium itself, so can be both charming or abstract.

These concept illustrations for Disney's 101 Dalmations (1961) disregard geometric concepts to purposefully create images that break drawing principles, such as perspective and form, but in doing so draw attention to the idea itself, allowing the viewer to enjoy translating these bizarre images. Colours are also very carefully selected and restricted to a fitting palette that doesn't detract from the mood of the image, or seem obscure. To me, the best part of it all is that this rule breaking was completely intentional and not the result of poor design or construction. This allowed the animators much more freedom to experiment and create dynamic characters and actions, unlike in Loonatics.

Several contemporary superhero cartoons have made great use of this aesthetic, such as in these layout design's for Samurai Jack (2001) by painter Lou Romano.

Or for concept work in The Incredibles (2004).

I love how the chaotic nature of the images from Samurai Jack really emphasise the dreadful monolithic structures on which they focus, distorted, jagged and threatening, with loud, but limited colours that grab attention. Similarly, these concept images from the Incredibles effortlessly translate ideas to an observer in a glance, without the need for extreme detail.

In the end, this idea for an aesthetic may only apply to my layout designs and not to characters, but this is still undecided. As this week progresses I hope to upload some experiments with these ideas in order to finalize both my film's visual style and designs.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)